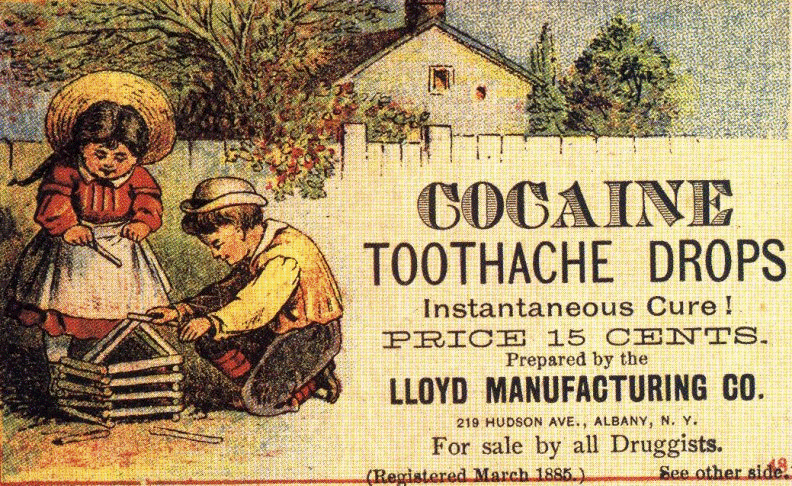

Cocaine tooth drops…clinically effective? Probably not.

In 1962, the FDA amended the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act to include the Kefauver Harris Amendment. This required that all pharmaceutical companies prove that their drugs were effective and safe for use before they could be approved. The disclosure of possible side effects and drug efficacy were also required and drug companies were banned from marketing generics as expensive, new, and/or breakthrough drugs as a result of the amendment.

Bye bye cocaine tooth drops.

What is Clinical Effectiveness?

Simply put, clinical effectiveness is how well a treatment works in everyday practice.

Effectiveness includes not only the drugs and pharmaceuticals you’re probably used to reading about in effectiveness studies, but the effectiveness of diagnostics, devices, procedures, and other interventions in clinical practice as well.

How Does Effectiveness Differ from Efficacy?

Effectiveness builds off of efficacy and safety.

Efficacy is how well a treatment works under “perfect adherence and highly controlled conditions” while effectiveness demonstrates how well a treatment works under normal conditions. So, you can think of effectiveness as how well a treatment works in the real world and efficacy as how well a treatment works in “perfect” conditions.

Also of note, while efficacy is measured in explanatory trials, effectiveness is measured in pragmatic trials.

How is Effectiveness Determined?

Effectiveness is determined by completing more than one well-controlled and adequate investigation, usually in the form of a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) that provides independent substantiation of experimental results. A single clinical experiment that determines efficacy is not enough to prove effectiveness.

To show effectiveness, results of the clinical experiment should be able to be replicated. However, the FDA notes that “studies that are of different design and independent in execution, perhaps evaluating different populations, endpoints, or dosage forms” may be as or more convincing then a study replication. Additionally, new treatments seeking approval must provide a certain quantity of evidence needed to establish effectiveness and documentation of said evidence.

If you’d prefer a bit more of a technical response, here is an introduction to determining effectiveness by Gartlehner, Hansen, and Nissman.

“Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are the gold standard in evaluating the effects of treatments. To be clinically meaningful, results must be relevant to specific patient populations in specific settings. Multiple factors determine the external validity (i.e., generalizability or applicability) of RCTs: patient characteristics, condition under investigation, drug regimens, costs, compliance, co-morbidities, and concomitant treatments. For practical reasons, trials cannot always take these factors fully into consideration (e.g., costs, poor compliance). Also, certain aspects of study design—eligibility criteria, study duration, mode of intervention, outcomes, adverse events assessment, or type of statistical analysis greatly influence the degree of generalizability, given an appropriate population of interest.”

The Future of Effectiveness Research

With the adoption of Electronic Health Records and more health data than ever being captured through technology, user devices, and connected data, effectiveness research may soon adapt to include new methods and strategies outside of the randomized control trials commonly used for effectiveness.

Some needs and discussion points in support of advancing research in effectiveness are noted below:

Issues Motivating the Discussion

(from Institute of Medicine Roundtable on Value & Science-Driven Health Care, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK51004/)

- Need for substantially improved understanding of the comparative clinical effectiveness of healthcare interventions.

- Strengths of the randomized controlled trial muted by constraints in time, cost, and limited applicability.

- Opportunities presented by the size and expansion of potentially interoperable administrative and clinical datasets.

- Opportunities presented by innovative study designs and statistical tools.

- Need for innovative approaches leading to a more practical and reliable clinical research paradigm.

- Need to build a system in which clinical effectiveness research is a more natural by-product of the care process.

References & Resources

Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Nissman D, et al. Criteria for Distinguishing Effectiveness From Efficacy Trials in Systematic Reviews. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2006 Apr. (Technical Reviews, No. 12.) 1, Introduction. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44024/

Hernán M, Hernández-Díaz S. Beyond the intention-to-treat in comparative effectiveness research. Clinical Trials [serial online]. February 2012;9(1):48-55. Available from: CINAHL Complete, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 10, 2014.

Institute of Medicine (US) Roundtable on Value & Science-Driven Health Care; Olsen LA, McGinnis JM, editors. Redesigning the Clinical Effectiveness Research Paradigm: Innovation and Practice-Based Approaches: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2010. Summary. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK51004/

Rothwell P. External validity of randomised controlled trials: “To whom do the results of this trial apply?“. Lancet [serial online]. January 2005;365(9453):82-93. Available from: Business Source Complete, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 10, 2014.

[GARD]